Integrating Maia2 (The Human-Like Chess Engine) into My Chess Application

A beginner-friendly look at human-style AI, neural networks, ONNX models, opening books, and everything that went into making Maia playable inside the platform.I have been working on chess applications for a little while, and one idea in my Discord community sparked a new and interesting challenge: what if we integrated Maia 2, a human-like chess AI, directly into the Chessboard Magic Repertoire Builder?

The idea was simple: instead of always practicing against Stockfish or relying only on database statistics, users could play and work with an AI that behaves like a real human at different rating levels. That single suggestion started a deep technical journey.

In this blog, I am going to walk through what Maia is, how it works under the hood, how I ran it directly inside a browser, how I solved the opening-move problem, and how everything fits together inside the Repertoire Builder.

My goal is to make this accessible even if you have never worked with AI models before.

What Is Maia?

Before diving into the implementation, it helps to understand what Maia actually is. Maia is an open-source chess engine created by researchers at the University of Toronto and Microsoft Research. Unlike Stockfish — which tries to find the strongest moves — Maia has a completely different goal:

Maia tries to predict the move a human would make.

Not the best move. Not the computer-perfect move. The human move.

Maia is built using a neural network, which is a type of computer model inspired by how the brain recognises patterns. Instead of calculating millions of positions like Stockfish, neural networks “learn” from examples. The Maia researchers trained the model on millions of real human games from Lichess.

That means:

- There’s a Maia-1100, trained on games by 1100-rated humans

- A Maia-1500, trained on 1500-rated players

- A Maia-1900, and so on

Each version learns how humans at that level actually play:

- The mistakes they make

- The patterns they recognise

- The blunders they fall for

- The openings they choose

- The tactical ideas they overlook

This is why playing Maia feels strangely familiar. It does not blast you off the board like Stockfish. It plays reasonable moves, gets ideas right or wrong the way you might expect from a real opponent, and its style changes depending on which rating bucket you choose.

For a tool like the Chessboard Magic Repertoire Builder, this makes Maia a perfect fit.

A Beginner-Friendly Primer on Neural Networks

You do not need deep machine learning knowledge to understand how Maia works, so here is a simple explanation.

A neural network is a system that learns patterns from many examples. Think of teaching a child to recognise a dog:

- You don not give them a rule book.

- You just show them lots of dogs.

- Eventually, they recognise the pattern.

A neural network works similarly, except instead of pictures of dogs, Maia sees:

Position Human move played

It sees this millions of times, and slowly learns:

- “In this kind of position, humans often push this pawn.”

- “At this rating level, players blunder this tactic often.”

- “People overlook this knight move.”

Instead of memorising openings or calculating tactics perfectly, the model develops intuition based on the patterns from human games.

This is why Maia feels human. It is not trying to be correct, it is trying to behave like the players it learned from.

How Maia Thinks: Inputs, Tensors, and Logits

Explained simply, without heavy math

When we ask Maia to calculated the candidate moves for a position, a few things happen behind the scenes. Neural networks cannot “see” a chessboard visually. They do not understand pieces or squares. They only understand numbers, so there are a few steps we need to consider:

Step 1: The Chessboard Becomes Numbers

We take the entire position and convert it into a structured set of numbers called a tensor. A tensor is just a multi-layered grid of numbers. Think of it as a digital spreadsheet that describes:

- Which squares contain which pieces

- Whose turn it is

- Castling rights

- En passant possibilities

- Move counts

- Recent moves for context

The network was trained on this exact type of input, so preparing it correctly is critical.

Step 2: The Neural Network Processes the Position

Once the chess position has been converted into numbers, those numbers are passed into Maia’s neural network. A neural network is made up of many layers, each of which transforms the input slightly. You can think of these layers as a sequence of filters:

- Early layers pick up simple patterns like “this piece is attacked” or “these squares are controlled.”

- Middle layers start combining these into richer patterns: pawn structures, piece coordination, tension, open files, typical human mistakes, and so on.

- Deeper layers blend all of this information into an overall understanding of the position from a human perspective.

By the time the input has passed through all the layers, the network has turned raw board information into a set of predictions about what humans tend to play in similar situations.

Step 3: The Output Is a List of Scores

The final output of the network is not a move like “e2e4.” Instead, the model produces a long list of scores, one score for every move it knows about. These scores (often called logits) show how strongly the model believes a human would pick each move.

For example:

- A high score means “humans often choose this move from this position.”

- A low score means “humans rarely choose this move.”

It’s important to note that the model simply assigns scores; it does not check whether the moves are legal. That comes next.

Step 4: Filter Out Illegal Moves

Because the model does not understand the rules of the current position, some highly rated moves might not make sense—for example, moving a knight that isn’t on the board anymore.

To fix this, we generate the list of legal moves from the actual board position and then:

- Remove all moves from the model’s output that are illegal.

- Keep only the legal ones.

- Re-scale the remaining scores so they form a clean, comparable list.

This step ensures the model’s predictions match reality and that we never show or play impossible moves.

Step 5: Display or Play the Human-Like Move

After cleaning the output and sorting the scores, the move with the highest remaining score becomes Maia’s chosen move—the one it believes a human is most likely to play.

Inside the Repertoire Builder, this result is used in two ways:

- In analysis mode: the move is displayed so users can study it.

- In practice mode: the move is played directly on the board so you can face Maia as your opponent.

Reproducing this entire pipeline accurately is essential, it ensures Maia behaves exactly the way the original researchers intended, delivering genuine human-style predictions inside the platform.

Running Maia in the Browser: The Model, ONNX, and Move Lookups

After understanding how Maia interprets positions and produces predictions, the next challenge was making it run directly inside a web browser. That means no server, no GPU, no backend processing, everything happens on the user’s device.

This approach keeps the experience fast, private, and scalable, but it requires a model format and runtime that can operate efficiently in JavaScript. Fortunately, Maia’s open-source ecosystem already supports this.

The Maia ONNX Model: One File for All Rating Buckets

Maia was trained on different rating groups (1100, 1300, 1500, etc.), and each of these rating buckets has its own move list and its own behavioural tendencies. However, the model itself is provided as a single ONNX file in the Maia Frontend GitHub repository.

This is incredibly convenient because:

- You do not have to load multiple model files.

- You do not have to swap models when the user changes Maia’s playing strength.

- The entire system works from one shared source.

Instead of separate model files, Maia uses a single neural network that supports all rating levels. The rating is chosen by passing a number (the rating bucket) into the model input during inference. This makes the integration much lighter and avoids complex resource management.

One model. One file. One setup.

What ONNX Actually Is

To understand why this works so well, it helps to know what ONNX is.

ONNX stands for Open Neural Network Exchange, and it is essentially a universal file format for machine learning models. The whole point of ONNX is portability, you can train a model in one framework (like PyTorch or TensorFlow) and run it almost anywhere else, including inside a browser.

A simple way to think about it:

.mp3is a universal audio format..pdfis a universal document format..onnxis a universal AI model format.

This means the exact same Maia model that the researchers built can be run directly in JavaScript without rewriting the network or converting anything manually.

ONNX Runtime Web: Running the Model in JavaScript

To execute the model inside the browser, I use ONNX Runtime Web, which is a JavaScript library designed specifically for running ONNX models efficiently on normal devices.

When you load Maia in the Repertoire Builder, ONNX Runtime Web is doing the heavy lifting. Its job is to:

- Load the Maia ONNX model file (the trained neural network).

- Accept the input tensor, which is the chess position converted into numbers.

- Run the forward pass of the neural network, this is Maia “thinking.”

- Return the prediction scores for every move the model knows.

The key advantage is that:

All of this computation happens on the user’s computer, not my server.

This means:

- No server costs

- No latency

- No scalability issues

- No privacy concerns

Maia can run offline once loaded, just like any other part of the app.

Move Lookup Files: Connecting Model Output to Real Chess Moves

Here’s a detail that surprises most people:

Maia never outputs moves like “e2e4.”

Instead, the model outputs a number — an index into a predetermined list of moves.

To handle this translation, Maia provides two essential files:

all_moves.json (index move)

This file is a long list of all moves the model was trained to understand.

For example:

0 "a2a3"

1 "a2a4"

2 "b1c3"

...

So when the model outputs something like 1572, the app looks up entry 1572 in this file to get the move string.

all_moves_reversed.json (move index)

This is the inverse mapping:

"a2a3" 0

"a2a4" 1

"b1c3" 2

...

This file is used when creating inputs for the model, for example, when telling Maia which moves were just played so it can build its internal context correctly.

Together, these two files ensure:

- every model output maps to a valid UCI move string,

- every UCI move can be converted back to the model’s internal index,

- and the system stays perfectly aligned with the data the model was trained on.

Without them, the model’s output would be meaningless numbers.

Why Maia (and Most Engines) Need an Opening Book

One important limitation of neural network engines, including Maia, is how they handle the opening phase of the game. The opening is a special moment in chess. All pieces start on their original squares, the board is perfectly symmetrical, and there are very few patterns for the model to recognise.

Neural networks rely on patterns to make predictions. When the position is still too simple, the model has very little to work with. This can lead to:

- random looking moves

- inconsistent opening choices

- unusual pawn pushes

- moves that do not reflect typical human opening habits

This is completely normal. Most engines use an opening book to guide their first few moves. Engines perform better when they are given a structured start.

To create a stable and human-like opening phase for Maia, I use the Lichess Opening Explorer API. For every position within the first 10 ply (five moves each), I fetch:

- human move frequencies

- win, draw, loss statistics

- typical follow-up moves

This data reflects how real players handle the opening in millions of games. It gives Maia a strong, realistic foundation before handing full control back to the model.

The result feels natural and avoids strange early blunders or unexpected opening choices.

Bringing It All Together

Integrating Maia into the Repertoire Builder became one of the most interesting projects I have worked on. It required understanding how human-style models behave, how to run AI directly inside the browser, how to map model outputs to real moves, how to build an opening foundation, and how to deal with the unique quirks of neural network chess engines.

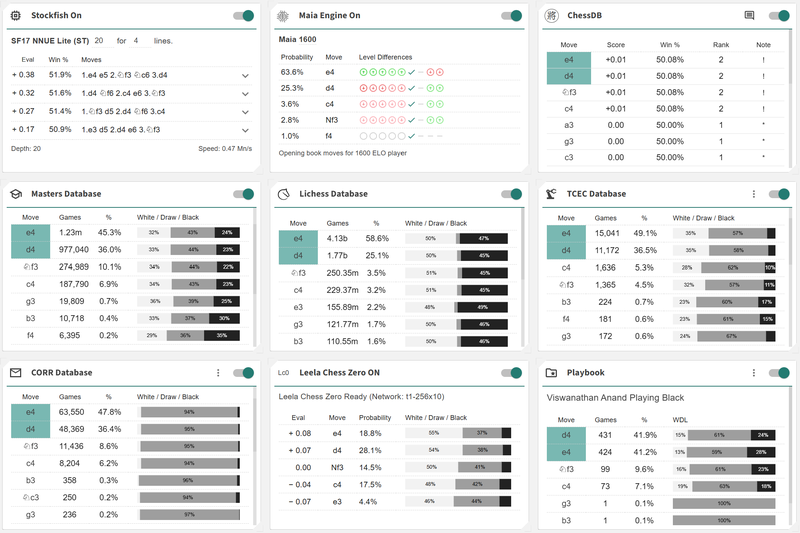

Inside the Repertoire Builder, Maia fits naturally. It complements the existing tools perfectly and adds a new dimension to the platform. Stockfish offers perfect tactical calculation. ChessDB and Lichess data provide large scale human statistics. Maia brings natural, human-like decision making. Together they create a training environment that feels complete, precise when accuracy matters, and realistic when you want to face something that behaves like a real opponent.

For me, this project was a chance to take a research model and turn it into something practical, responsive, and genuinely helpful for everyday chess players. The result is an opponent that users instantly recognise. It plays moves that feel human. Sometimes sharp, sometimes creative, sometimes flawed, but always natural.

I hope you found this breakdown interesting and that it helps you understand what makes Maia special. Whether you are building a training tool, experimenting with human-style AI, or simply curious about how modern models work, Maia is a great project to explore.

I also hope you will try integrating it into your own applications and see what unique experiences it can create for your users. Do let me know what you think in the comments.

Kind regards,

Toan Hoang (HollowLeaf)

References

- https://www.maiachess.com - The official Maia Chess website.

- https://github.com/CSSLab/maia2 - The Maia Chess GitHub repository containing the model files, code, and research resources.

- https://github.com/CSSLab/maia-platform-frontend - A fully working open source frontend that shows how to integrate Maia directly into a browser application.

- https://onnx.ai - The official ONNX website, which explains the ONNX model format and ecosystem.

- https://onnxruntime.ai -The ONNX Runtime website, covering the runtimes used to execute ONNX models, including ONNX Runtime Web for browser-based inference.

You may also like

CM HGabor

CM HGaborHow titled players lie to you

This post is a word of warning for the average club player. As the chess world is becoming increasin… HollowLeaf

HollowLeafSuspicious Chess App Idea?

Suspicious Games, Engines, and Paranoia HollowLeaf

HollowLeafAI Chess Coaches?

Is It Possible? tolius

toliusAntichess: 1. e3 Wins for White in #79

The title of this blog is a reference to the 2016 article by Mark Watkins, “Losing Chess: 1. e3 wins… TotalNoob69

TotalNoob69Did you know Lichess can do this?! Opening Explorer and Tablebase

... do click on that little book button HollowLeaf

HollowLeaf