Measuring Level of Play in different Endgame Types

Using Stockfish to see which players improve their winning chances the most in different types of endingsEvaluating the performance of a chess player in different parts of a game is difficult because there are no points one can count to see who is ahead and by how much.

The closest thing to this would be using engines to analyse the positions at different points and see how the evaluation changed. So I had the idea to see how well players play different types of endgames by looking at how the engine evaluation changes.

Measuring performance in different endings

To evaluate how well a player played a certain type of endgame, I first used Stockfish’s WDL to calculate the expected score of the player when entering that type of endgame. I subtracted this value from the expected score after the type of endgame has changed (I used the score of the player in the game, if the game ended without changing endgame types).

So the metric is: expectedScoreAfter - expectedScoreBefore

This shows how much a player has improved or worsened their expected score while playing a specific type of endgame. For the later comparisons, I’ll divide this by the number of games, to make the different values comparable among the players.

In this post, I’ll be looking at the basic types of endgames, namely endgames where both players have only the same piece type left and pawn endgames.

Looking at different players

I decided to look at two different groups of players.

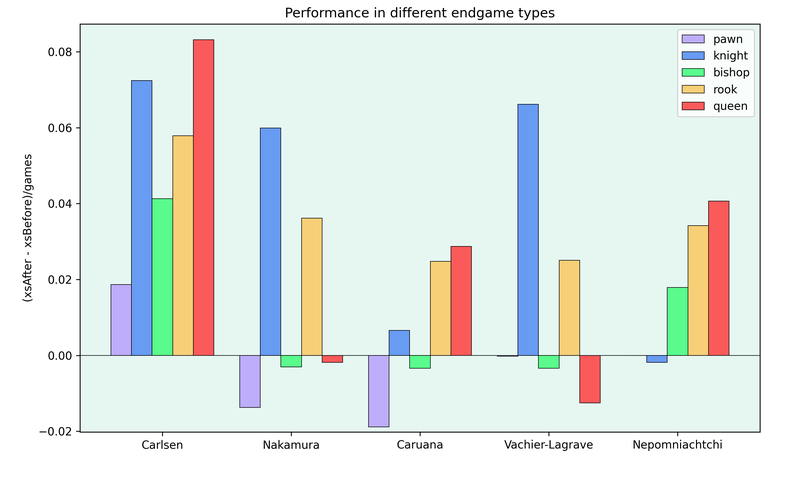

Firstly, I’m going to look at the top players from Carlsen’s generation. For this group, I only took classical games from 2012 onwards, to exclude any games when the players were younger and weaker.

In the graph, I show the difference between the expected score after a specific endgame type and the expected score before the endgame type, divided by the number of games. So, for example, Carlsen improves his expected score in bishop endgames by about 4% on average.

Unsurprisingly, it looks like Carlsen is doing well in all types of endgames. The results for the other players are more varied.

Both Vachier-Lagrave and Nepomniachtchi scored as well as Stockfish predicted in pawn endings, so their bars for these endings aren’t really visible.

Both Caruana and Nakamura score worse in pawn endings than Stockfish predicted. I think that one reason for this may be that there isn’t much wiggle room in these types of endings. When evaluating pawn endings, Stockfish either thinks it’s a win or draw, so one mistake can drag down the average a lot and it’s more rare to win a pawn ending that isn’t evaluated as completely winning from the beginning.

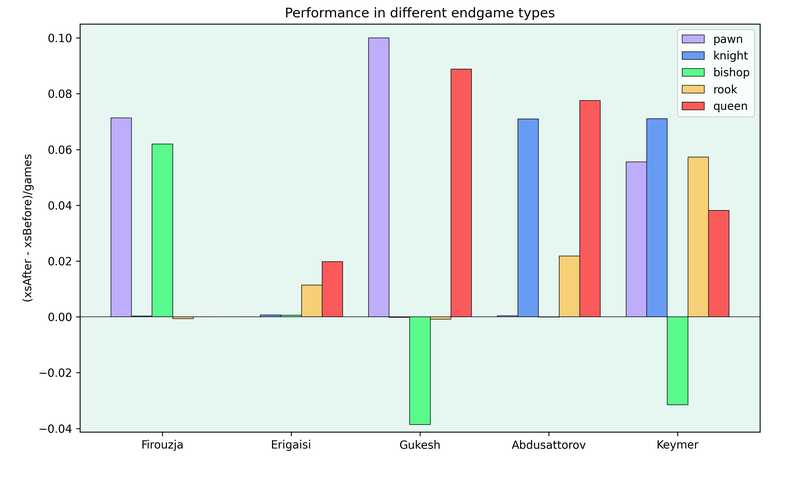

I also wanted to take a look at the new generation of players to see how they compare to each other. Again, I didn’t want to take any games from when they were very young, so I decided to only take games from 2022 onwards.

First of all, it’s important to point out that the sample size for the younger players is much smaller compared to the players from Carlsen’s generation. This probably results in Gukesh’s results being a bit all over the place. He scores very well in pawn end queen endings and very poorly in bishop endings.

Erigaisi has scored very similarly to the expected score by Stockfish, outperforming it slightly in major piece endings. The remaining players score very well in some endings and there are a lot more endings where the expected score of the players doesn’t really change.

Limitations

As I’m only evaluating the position at the start and end of each endgame type, all mistakes the players make during the endgames aren’t included. I did this mainly to make an analysis of thousands of games feasible, but I also think that looking at every move and averaging the result comes with its own problems.

For example, a player may throw away a winning position, but if they make a lot of moves in the resulting drawn position, they’ll get a better score than a player who made the same mistake, but agreed to a draw right away.

Also splitting the endgames into these categories may be a bit problematic. For example, a player may allow a trade of rooks in a rook endgame because they misevaluate the resulting pawn ending. My method would detect this as an error in the rook ending, while in reality the mistake occurs when calculating the pawn ending.

I’ve had similar situations in the past and I don’t have any solutions to these situations where the position on the board isn’t really the thing a player is thinking about. Let me know if you have any ideas about how to handle these situations.

You may also like

jk_182

jk_182The Candidates in 13 Graphs

Looking at stats from the 2024 Candidates tournament jk_182

jk_182How Opening Advantages Translate into Results in Online Games

Measuring conversion rates in online blitz and bullet games for 1200 to 2400 rated players jk_182

jk_182Evaluating Sharpness using LC0's WDL

Can engines tell how sharp a position is? CM HGabor

CM HGaborHow titled players lie to you

This post is a word of warning for the average club player. As the chess world is becoming increasin… jk_182

jk_182Predicting the Outcome of Chess Games

Approximating the expected score and draw rate based on rating difference and colors jk_182

jk_182