The 5 Stages of Chess Mastery

Where are you?Most chess advice fails because it isn’t for the right stage.

There are five stages of chess mastery and each one needs a different focus.

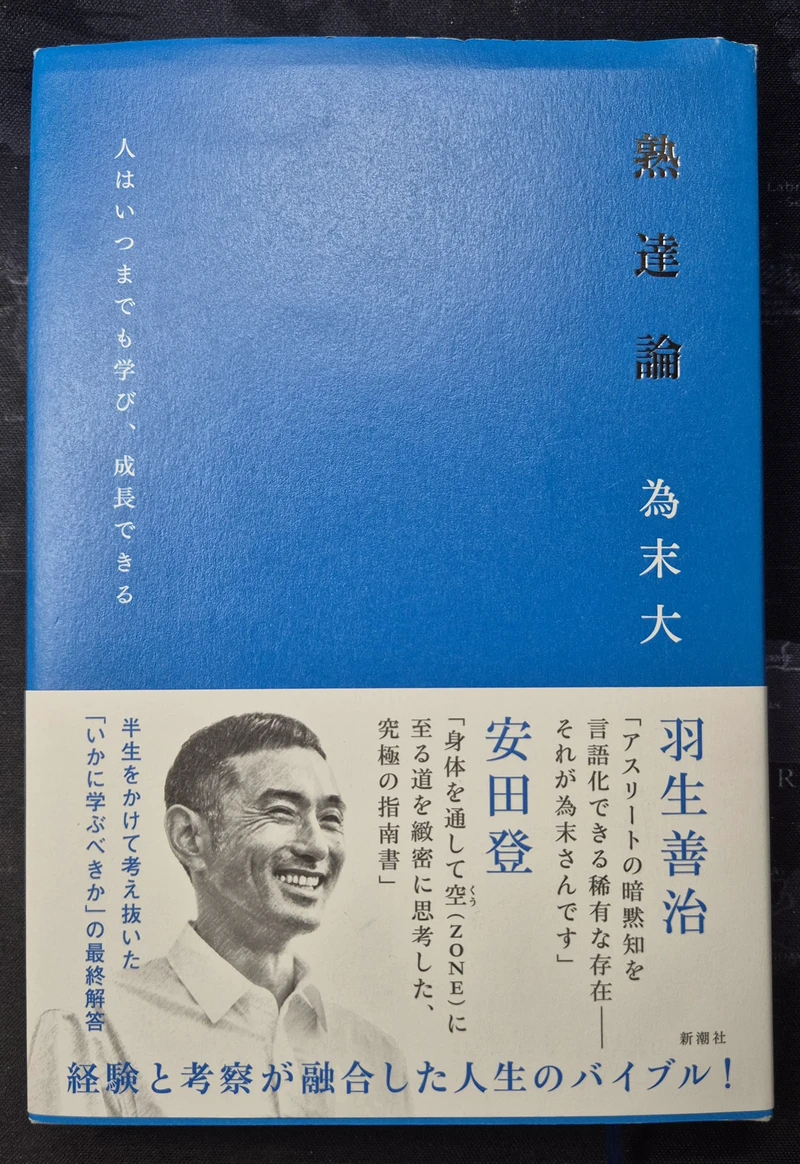

This idea comes from a Japanese book, 熟達論 (Jukutatsuron), often translated as The Theory of Mastery.

The author of the book, Dai Tamesue was a 400m hurdler and the first Japanese sprinter to medal at the World Championships. His nickname is ‘The Running Philosopher’. The book hasn’t been translated into English so unless you read Japanese, you’re seeing these ideas here for the first time.

In this post I’ve applied the five stages to chess so you can figure out which stage you’re in right now and what to work on next.

But this isn’t just about strength. It’s also about your relationship with chess. That’s why a master might need to return to Stage 1 and a beginner can sometimes get a glimpse of Stage 5.

Stage 1 is Play (遊).

This is where everyone starts. You play because you want to play.

You learn how the pieces move, you try to checkmate someone, you get checkmated. Then you play again.

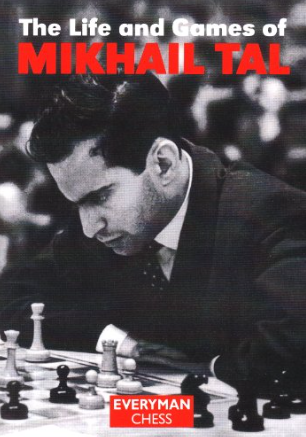

Mikhail Tal said in his autobiography that learning chess is like catching the flu.

Such a man walks along the street, and he does not yet know that he is ill. He is healthy, he feels fine, but the microbes are doing their work.

...

A few days pass, and suddenly you involuntarily begin to sense that, without chess, there is something missing in your life. Then you may rejoice: you belong to that group of people without a natural immunity to the chess disease...

In Stage 1, you aren’t really thinking about improvement. But you still get stronger. You try things, they work or they fail and you think, “why did that happen?” That question is where learning starts.

But the problem with only playing is that you eventually hit a limit. You might even play the same bad first move every game and never notice why it’s bad.

So at some point, you branch out. You watch videos, read books, hire a coach. And the reason you play shifts: you start playing to get better, not just for fun.

Of course, wanting to improve isn’t the problem. The trap a lot of people fall into is trying to optimise too early.

Many adults who get into chess often treat it like a project rather than a game. They feel like every minute has to have a purpose and feel guilty if they play “just for fun”.

But if you treat chess like a project from Day 1, you can miss the rewards of this first stage.

Imagine it’s your first day playing tennis. You don’t even know how to hit the ball yet, or what a proper swing feels like. But you already start drilling your perfect forehand.

You should just start with hitting the ball, fullstop. It’s easier to improve your forehand after you’ve learnt how to hit the ball consistently.

Chess is the same.

If you’re only thinking of playing correctly, you stop noticing what’s right in front of you. Instead of pausing to think about why a move didn’t work, you rush to the next item in your training plan.

I’ve seen examples of this as a coach.

- Instead of realising that their knight is attacked by a pawn in the opening, a player tries to remember the next move from an opening course.

- Or, a player wants to try the King’s Gambit because it looks fun, but they don’t because they avoid any moves that make the eval bar go down. Then they miss the chance to learn how attacks can compensate for material.

Stage 1 is where your aim is to play, not learn.

And the idea of Play is something that’s important throughout your chess journey.

It becomes a mindset you return to.

Maybe my all-time favourite line in chess is from the end of Tal’s book, where he’s interviewing himself as a journalist.

...That is my biography from the first day of my chess life to the present.

JOURNALIST. And your plans.

PLAYER. To play!

So if you feel stuck, depressed or anxious, come back to Play. Play for a few days just for fun. Try new ideas and forget about results. That’s often enough to bring your motivation back and enjoy chess again.

So in Stage 1, know the limits of only playing, but don’t forget its importance either.

Stage 2 is Form (型).

In Japanese, this is called kata. In martial arts, kata means a set form you practice again and again until it becomes natural.

In chess, these would be the basic skills and principles. You learn patterns that are important in every game and you train them until they become automatic.

Some examples are simple checkmates, noticing when pieces are hanging and developing your pieces in the opening.

In Stage 2, you drill these patterns until they become habits. That’s important because habits shape what you notice and what you notice shapes the moves you play.

Basic doesn’t mean easy. It’s “basic” because it becomes the base of everything else.

When you’ve got a solid base, you spend less effort on simple things and have more space in your head to think.

Many chessplayers get stuck here. There are three big reasons for this.

First, you underestimate the basics.

You try to think or play like an advanced player too early.

You watch videos about strategy and get obsessed with deep plans when you’re still hanging pieces in every game. You need to fix that first. Patterns only stick after a lot of reps.

So don’t rush and go to Level 50 before mastering Level 10. For example, if you’re rated under 1500 online, the Hanging Pieces theme on Lichess is great to drill.

Second, you learn the basics but you can’t use them in your games.

You can spot tactics quickly in puzzles but you miss them completely in games, yours and your opponent’s.

That means you need more targeted training to turn your patterns from knowledge into skill. For example, you can play through the games and guess the moves of players like Paul Morphy. He’s great at active play, so by paying attention to how he positions and improves his pieces to set up attacks and tactical chances you’ll improve your awareness.

Third, you spend too much time on the wrong things.

People spend hours on opening theory when they’re still making big tactical or positional mistakes.

At the amateur level, openings matter but fundamentals matter more. You can watch streams or speedruns where strong players talk out loud about how they think about positions and decide on a move. Try to absorb the principles and ways of thinking rather than specific moves, and apply them when you play.

Stage 2 is where you build your base, learning patterns and principles that you need in every game.

When your Form is strong, everything that comes after gets easier.

Stage 3 is Observation (観).

This is where you go from “I know patterns” to “I understand positions.”

You start seeing beyond what’s on the surface, not just the whole but all its parts.

You can look at a position, ask yourself “what matters most here?” and work it out.

By now, you’ve honed the fundamentals further.

You can do things like find combinations with several tactical patterns and think of good candidate moves and plans for both sides. You can find exceptions to guidelines, such as taking on doubled pawns in the middlegame because the positives outweigh the negatives. (Below: from Botvinnik-Sorokin, 1931)

Most players spend a long time in Stages 1 to 3, and you can become very strong there. But Stage 3 is where many strong players get stuck.

You can explain positions but you’re not sure what the best move might be.

Or you might see the right move but it can take too long or you miss it under pressure.

Here are a few common mistakes at Stage 3.

First, a lot of players use engines the wrong way, and probably too much.

They know the engine likes a move but they can’t explain why, and they don’t put in any effort to dig deeper to understand what’s really happening in the position.

Second, when it’s their move, they jump into calculating a move immediately.

They don’t know how to slow down and consider alternatives, or why they should do that.

And third, they rely too much on their strengths but avoid things they aren’t comfortable with.

That can lead to weak areas and inconsistent performances that hold them back.

So in Stage 3, you need to take the time to not only learn about chess but your own chess. You’re now seeing a lot from experience, study and training. That’s why it becomes more and more important to find what you’re not seeing because that’s what you’re missing to get to the next level.

Improving in Stage 3 is harder than in Stage 2, because what you need to focus on is often something that doesn’t come naturally to you or takes a lot more training.

Here are a couple of approaches that’ve worked well in my own experience on the way to International Master and for students I’ve taught.

First, play serious classical games and analyse them with intention, especially the ones you lost.

Don’t just look through them quickly with an engine, use your own head. Find the critical moments yourself, come up with improvements, think about why you made a mistake and find recurring patterns from your games. The main thing is to find at least one takeaway from every game so you can improve one thing in your next game.

Second, work on both your strengths and weaknesses.

It’s normal to avoid the areas that feel scary but you don’t have to fix everything at once. Start with the smallest step, even learning one thing about it and try and apply it in a game. If you hate endgames and usually avoid exchanges, venture into the other extreme and try exchanging a lot of pieces in your online games for one week. Do this without any expectations and you often find that it can be pretty fun and liberating. You notice things you usually wouldn’t and you get comfortable with this thing that’s been triggering your flight response.

Talking to a coach or training partner can show you other perspectives and be a shortcut to figuring out what you’re not seeing. It’s also important to improve your practical thinking by regularly playing against stronger players.

So Stage 3 is about understanding your chess deeper, working on your strengths and weaknesses and continuing to improve your skills by exploring all areas of your chess.

But if we’re talking about mastery, there’s more.

Stage 4 is Core (心).

In this stage, you go from “I understand positions” to “I can sense what both sides should do.”

You look at a position and within 5 to 10 seconds you have a decent idea of what’s happening. You still need to double-check but you don’t need to build the whole picture from scratch. You can already sense what lies at the heart, or core of the position.

This comes from years of playing, training and studying. Now you not only have the basics but advanced skills and understanding too. Having a strong feel for the game frees up brain power for the most complex positions and difficult decisions.

This is also where your style becomes real. Because you can handle a wide range of positions while having a leaning towards what makes your chess yours, it comes out naturally.

You can play actively without losing control, play quiet positions without drifting and switch things up when the position demands it. Or you might still have some weaknesses, but you have strengths with which you can beat stronger players.

You’ve cut the excess from your decision making. And in your training, you can concentrate on difficult exercises because you know long term improvement comes from pushing yourself.

At this point, you’re a very strong player. You’ve likely competed for years and you’re either a master or someone who can compete with one.

But every stage has its pitfalls, and Stage 4 has a few.

The first trap is relying on your intuition too much.

Your game sense is strong so it’s tempting to be lazy. But at this level, small details decide games. You need to keep doing the hard training when no-one is watching. This might be calculation or doubling down on the areas of your game that get targeted by stronger players.

The second trap is entitlement.

You’ve put a lot of blood, sweat and tears into chess so part of you expects things to get easier now. The truth is that every 100 points gets exponentially harder. In an interview I did with Australian GM Moulthun, he put it like this:

At least for me, going from 0 to IM was much easier than going from IM to GM.

The third trap is getting too focused on results.

When you’re strong, you’ve already tasted success so you might be frustrated when things get harder. You need to set goals bigger than your short-term results so you don’t burn out.

It’s good to have even one person who you can be totally honest with and talk to when you’re down in the dumps. Having a support system helps you bounce back quicker.

This is where it helps to return to Stage 1 sometimes. Not to stop being serious, but to remember why you cared in the first place. Play a few games with curiosity again. Take more risks. Appreciate the fact that you have this game which can make you feel so many things.

Stage 5 is Void (空).

This is where you come back to playing for the sake of playing, but now you have the experience, skills and understanding. In earlier stages, your mind had a lot going on, trying to remember principles, spot tactics and not blunder all at once.

Here, it’s calmer. Those core skills are already a part of you so you can focus on finding the best moves in the position.

Some people call this being “in the zone”. Your ego falls away and you aren’t thinking about your rating or what the result of this gam will mean. You’re focused on the board, on the problem you have to solve and nothing else matters.

This can sound a bit abstract but in chess terms it’s simple. You see what matters quickly, you stay present and perform at your highest level.

Easy to say, hard to do consistently.

It can also feel like the passing of time changes. Each moment feels sharp and clear, and the game feels like it was both over in an instant while also going for days.

You don’t have to be a world-class player to get a glimpse of this. Even as a beginner, you might have felt it. You start playing a few games after lunch, you’re completely hooked and next thing you know it’s dark outside.

Even Stage 5 has a trap.

If you still compete, you still have to do the work to stay sharp. It can be hard to hold the same edge when you’re less attached to winning because a lot of players built their strength from hunger and obsession.

So you want to find a way to keep training and competing actively, putting everything you’ve learnt and absorbed through your chess life into your next move.

And that’s Stage 5. It isn’t a finish line. It’s a way of living both on and off the board.

When someone is young, he is not capable of conceiving of time as a circle, but thinks of it as a road leading forward to ever-new horizons; he does not yet sense that his life contains just a single theme; he will come to realise it only when his life begins to enact its first variations.

—Milan Kundera, Immortality

Which stage are you in in your chess journey?

You may also like

IM datajunkie

IM datajunkieThree signals of future strength in chess

Trainable behaviours I noticed while giving a simul at the Australian Juniors IM datajunkie

IM datajunkieDo this on your opponent's turn

5 simple habits to use your time better and level up your chess IM datajunkie

IM datajunkie25 lessons from 25 years of chess

Mistakes you can avoid and habits you can start with today IM datajunkie

IM datajunkieWhy your tactics aren’t improving

The 4 fixes that can help you become a tactician CM HGabor

CM HGaborHow titled players lie to you

This post is a word of warning for the average club player. As the chess world is becoming increasin… nvasquez

nvasquez