Confidence: It’s Not Just About Playing Well... It’s About Believing You Can

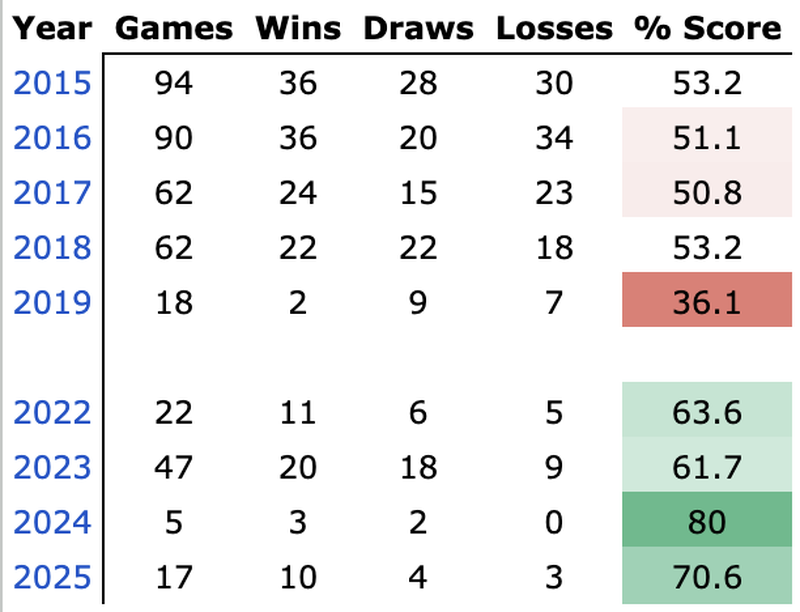

How to stop letting one bad move ruin your whole gameLast May, I earned the US Chess National Master title, crossing the elusive 2200 rating threshold. As an adult improver, this was a surreal lifetime achievement. I started playing chess in 2003 and earned the US Chess Candidate Master title in 2015 as a college freshman, breaking 2100 in the same year. But by the time I graduated in 2019, my rating had plateaued, and what once felt like a destined path to NM quickly took a back seat as I entered the workforce. To finally reach the summit after a decade of falling short was incredibly emotional, especially since I didn't believe I could earn the title when I started playing tournament chess again in 2022.

Here's the thing - I'm not convinced that I know more about chess than I did 10 years ago. Most chess literature and coaches point to some form of calculation (tactics, evaluating positions, etc) and intuition (positional concepts, strategy, endgame) as the two primary levers to growth and rating progression. I'd like to propose a third: confidence.

Confidence doesn’t replace chess knowledge, but reflecting on my journey to National Master, I believe that building and maintaining a healthy growth mindset made the biggest difference in my over-the-board performance. With this new outlook, I am much better at playing chess than I was in 2015.

What Makes a "Good Game"?

Many tournament players ask themselves some form of the question "Did I play a good game?" after every game, regardless of the result. When I was younger, I believed that I could say that I played a good game if I:

- Built a small advantage in the opening or early middlegame

- Gradually improved my position while actively targeting my opponent's weaknesses

- Converted the endgame from the position of strength without allowing significant counterplay

I found success with this "total domination" framework, and the emphasis on endgames was a key part of my growth around the time I earned the Candidate Master title. Converting small advantages in such a manner is an incredibly high bar, so setting these wins as the threshold for playing "good chess" and being proud of your play is quite natural.

Here's another example from my 1st place finish at the 2023 Liberty Bell Open (U2100 section). In this game, my opponent allows me to quickly build a Stonewall set-up and launch a kingside attack that resulted in a relatively smooth endgame conversion.

It's important to know how to win games like these, but deeming these types of wins as meeting the benchmark for "good games" is a flawed approach. In the first game, my opponent didn't offer any significant active resistance to my piece placement, even allowing me to march my king to b3 before I executed my plan. In the second game, my opponent wasn't familiar with the opening and lost critical time playing 13...Rab8 and 14...Be8, culminating in a lethal kingside attack for White.

This begs the question: what happens when your opponent doesn't make a small inaccuracy in the opening? What happens if they drum up enough counterplay and complicate the position such that "total control" of the game isn't possible or beyond your means of calculation?

Consistently dominating games across all three phases of the game isn't a realistic bar, and if it is happening, it may mean you're playing against inferior competition relative to your own strength. Yes, absolutely punish your opponents for making tactical or positional blunders - but don't count on your opponents to make mistakes to meet your intrinsic standard of "playing good chess". To improve, you have to be comfortable being uncomfortable. And more importantly, you have to enjoy it.

Thus, when I returned to tournament play in 2022, I concluded that to truly enjoy my games, I needed to expand my narrow view of what a "good game" was.

Good Moments > Good Games

To help contextualize this, consider Roger Federer, arguably the greatest tennis player of all time. As he shared in a 2024 commencement speech at Dartmouth University: "When you're playing a point, it has to be the most important thing in the world, but when it's behind you, it's behind you." A winner of 20 major open titles and a top-ranked tennis player by the Association of Tennis Professionals for 310 weeks, Federer still only won 54% of the points he played throughout his career.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_ILk8Yai3Wo

I think chess has many similarities with tennis. Unless you're a top-rated player, it's incredibly difficult to play a game in which the computer finds no errors in your decision-making. Even in games where you're able to control all three phases of the game, the engine will often come up with challenging defenses that you may not have considered. TLDR, you're going to make mistakes.

The first step in building a growth mindset in chess is to stop tying self-evaluation to a game result or a single blunder. Instead of focusing on playing a single "good game", focus on creating many "good moments".

A "good moment" can be broadly defined, but a couple of examples from my own experience:

- Making a good move/series of moves that improves your position or puts pressure on your opponent.

- Finding a resource that your opponent either didn't consider or didn't know how to respond to once played over the board.

- Identifying a long-term plan that simplifies your decision-making process for the rest of the game.

- Accurate calculation of a complicated line with a clear evaluation of the final position (even if the line is not played over the board).

- Making a practical decision in the presence of multiple appealing candidate moves.

- Consistently finding strong defensive resources in a worse position.

- Managing time particularly well throughout a critical phase of the game without compromising your position.

- Handling time pressure well, without letting emotions cloud your judgment.

- Knowing the opening better than your opponent, either resulting in a better position or an advantage on the clock.

- Anything that happens during a game that makes you feel more confident (ie, your higher-rated opponent offers a draw, opponent's negative body language, etc)

This is hardly a definitive list, and may change from game to game. Some games may offer more moments than others, but removing the stress of wanting to play a "good game" allows you to focus on just creating the next "good moment". The point of this approach is not to scrutinize every decision you make throughout a game, but rather to balance giving yourself credit for what you're doing right versus your desire to play better chess. Remember, you're going to make mistakes.

This means it's possible to lose a game where you created a lot of good moments. Great! The sooner you can be proud of your losses, the sooner you can both build confidence playing against strong opponents AND be completely objective when evaluating where things went wrong post-mortem. Here's an example from my library:

There are two possible outlooks to a game like this:

- Bad Game Outlook: "I was better the whole game, but I threw it all away with some bad blunders in time trouble. I should have been able to press for more!"

- Good Moment Outlook: "I thought I created a lot of pressure early, and that led to a middlegame where I thought I made a lot of good strategic decisions. I spent a little too much time in non-critical positions, and I simply didn't have enough time left in the end to build on my advantage. I thought overall I played well, but my opponent played a really good game too."

Realistically, how many of us have had the "Bad Game" outlook in this specific situation? These two outlooks are virtually identical in interpretation, but the framing makes a world of difference. The "Bad Game" outlook is 0/1, the "Good Moment" outlook is 3/4. It's a lot easier to convince yourself in such cases that you're almost playing at a higher level when you're starting from a place mentally of already doing so much right, rather than fixating on everything you did wrong. It takes a lot of persistence, but over time, you learn to fight for good moments, even during games when all seems lost.

Flash forward to the Maryland Open earlier this year, where I earned my National Master title. Paired against GM Larry Kaufman in the second round, I had a nightmarish start to my day. At 6 AM, a hotel staffer mistakenly came into my room, startling me and ensuring a good night's sleep was impossible. I caffeinated as much as I could before the start of the round to compensate, but after a reasonable opening position crumbled, I was staring down the barrel of a rout. Everything was going wrong.

Frustrated, tired, and disappointed that an opportunity to play a GM may go to waste, I stayed vigilant and focused on creating as many good moments as I could in a worse position. It wasn't pretty, but I scored my first-ever win against a Grandmaster:

Sure, many players would consider this to objectively not be a "good game" by me - I agree. But I'm also not going to rationalize away my first-ever GM scalp into a disappointing performance. When I look back at this game, I reflect on the good moments I created in the endgame to overcome adversity, while also now having the opportunity to deepen my understanding of these opening lines where I was clearly underprepared. As a result, I've since "leveled up" my understanding of these ...Ba6 lines, but am also more confident in my ability to play complicated endgames against higher-rated players.

Closing Thoughts

As I prefaced at the beginning of the article, building confidence through a growth mindset is not a replacement for actual chess knowledge. If anything, self-reflection and introspection in chess are a repackaging of what you already know, while also setting a realistic and healthy bar for performance, given that playing perfect chess is simply unattainable for humans.

In my youth, growth seemed simple - plug your tournament games into the computer, turn on the engine, and focus on major evaluation bar swings. With ample time as a student, agonizing over every slight mistake felt like a necessity to get better, and was justified by the amount of time I had to study chess.

When I returned to tournament play in 2022, I had virtually no expectations as I was working full-time and juggling GRE test prep ahead of a demanding MBA application process. Most weeks, I'd be lucky to dedicate 2-3 hours to studying, so I had to adapt to the "Good Moments" mindset. Not just to focus on incremental growth, but to keep a positive and fun relationship with the game as I balanced my other life priorities. What followed was my most significant growth in rating and results in over a decade.

As I've become more comfortable with this new lens in my play, it's also been easier to find top-level games that inspire me as a spectator. While I still appreciate a "total domination" performance, I'm now far more impressed when a player can "breakthrough" from an equal or unclear position over a series of just a few moves - even if the rest of the game is hardly exemplary. A classic "good moment".

Over the next few months, I'm hoping to continue writing about building and maintaining a healthy growth mindset, and how I was able to tweak my over-the-board decision-making to finally crack the 2200 rating barrier. Given the unique perspective I've built, I don't expect my outlook to resonate with everyone, but for players who feel stuck and discouraged, perhaps my experiences may offer a beacon of hope.

Do you have your own experiences where a shift in mindset yielded better results? Share your thoughts and stories in the comment section below. If you want to stay up-to-date on my future articles, make sure to follow my account.

You may also like

FM MathiCasa

FM MathiCasaChess Football: A Fun and Creative Variant

Where chess pieces become "players" and the traditional chessboard turns into a soccer field GM Avetik_ChessMood

GM Avetik_ChessMood10 Things to Give Up to Enjoy Chess Fully

Discover how embracing a lighter mindset can help you enjoy chess again and achieve better results. CM HGabor

CM HGaborHow titled players lie to you

This post is a word of warning for the average club player. As the chess world is becoming increasin… NM isaackaito

NM isaackaitoThe Confidence Formula: Training to Narrow The Gap Between Your Best and Worst

Growing over-the-board confidence stems from developing a consistent foundation you trust NM isaackaito

NM isaackaito"Play Till Kings": How I Became a National Master by Declining Draws

How Saying “No” Transformed My Game And Why You Should Do the Same ChessMonitor_Stats

ChessMonitor_Stats