The 4 Questions Strong Players Ask on Every Move (That You Probably Skip)

A simple thinking system to reduce blunders and find better movesYou didn’t lose that last game because you don’t know chess.

You lost because your thinking process broke down for a move or two. Maybe three. That’s all it takes. One moment you’re playing solidly, the next you’ve hung a piece or walked into a tactic you should have seen coming.

Here’s what I’ve noticed after years of coaching and playing: the players who improve fastest aren’t necessarily the ones grinding the most puzzles or memorizing the deepest opening theory. They’re the ones who have a reliable mental checklist they run through on every single move. When that checklist becomes automatic, blunders drop dramatically and tactics flow

Today I’m sharing a simple, repeatable flowchart: four questions to ask yourself every turn. This isn’t some complicated system you need to study for weeks. It’s a practical framework you can start using in your very next game.

The Flowchart: Your 4 Questions

Before we dive into the reasoning, here’s the quick-reference version you can bookmark and use immediately:

Question 1: What did my opponent’s last move do? (threats + intentions)

Question 2: What forcing moves do I have? (checks, captures, threats)

Question 3: If nothing tactical: what improves my position most? (plan/pieces/weaknesses)

Question 4: Blunder check: how does my opponent respond to my move?

One important note: if Question 2 gives you something concrete (a winning tactic, a strong forcing sequence) you can often skip Question 3 entirely. The flowchart isn’t meant to slow you down unnecessarily. It’s meant to make sure you don’t skip critical steps.

Why Most Chess Mistakes Are Thinking-Process Failures

Here’s the core idea behind this entire system: nearly every mistake you make can be traced back to one of these four questions breaking down.

Think about your last painful loss. I’d bet serious money it falls into one of these four buckets:

Step 1 breakdown: You didn’t notice your opponent’s threat. You didn’t understand what changed in the position after their move. You were thinking about your own plans and missed that they just created a problem for you.

Step 2 breakdown: You missed a tactic. You had a winning combination available and didn’t even consider it. Or you saw something promising but miscalculated the forcing line.

Step 3 breakdown: You made a strategic inaccuracy. You chose the wrong plan. You improved the wrong piece. You had a quiet position and made a move that didn’t actually accomplish anything useful.

Step 4 breakdown: You failed to blunder-check. You found a move you liked, played it, and only after pressing the clock did you realize your opponent had a devastating response.

This framework gives you a language for diagnosing your errors. Instead of staring at your game afterward thinking “I’m bad at chess,” you can identify the specific step that failed and train it directly.

Step 1: “What did my opponent’s last move do?”

This is the most neglected step in amateur chess. We’re so focused on our own ideas that we barely register what our opponent just played. Their move becomes background noise while we execute our predetermined plan.

That’s how you hang pieces.

What you’re trying to detect:

First, look for direct threats. Is your opponent threatening checkmate? Have they attacked an undefended piece? Are they setting up a fork, a pin, a discovered attack?

Second, recognize that the position has changed. Did their move open a file? Create a weak square? Remove a key defender? Even quiet-looking moves can shift the balance in ways that demand a response.

Third, try to understand their plan. Even if they’re not threatening anything immediately, what are they building toward? If you can see two or three moves into their idea, you can often prevent it before it becomes dangerous.

Opponent just played: a4

What it threatens/changes: White gains more space on the queenside but more importantly, they want to advance the pawn even further with a5 to trap our b6-bishop

The “normal move” that blunders: Continuing with your planned ...0-0, missing that after a5, your bishop is trapped and lost.

The correct response: Recognize the threat and address the problem before continuing with your own plans. We can do this by playing ...a6 or ...a5

Mistake Diagnosis

If you blundered because you didn’t see the opponent’s threat, or you saw their move but didn’t understand its purpose, label it: Bucket: Step 1 breakdown.

Step 2: “What forcing moves do I have?”

Once you’ve assessed what your opponent is up to, it’s time to look for your opportunities. The most powerful moves in chess are forcing moves: they demand a response and limit your opponent’s options.

What counts as forcing:

Checks. Your opponent must deal with a check. This is the most forcing move type in chess.

Captures. Taking material usually forces a recapture or some defensive response.

Threats. Especially high-value threats like mate threats, attacks on the queen, or attacks on hanging pieces.

Two common failure modes:

Didn’t spot the tactic at all. You never even looked for forcing moves. You were thinking about slow maneuvering while a winning combination was sitting on the board. This is a habit problem: you need to train yourself to scan for checks, captures, and threats before considering anything else.

Spotted it, calculated it wrong. You saw the forcing sequence, started down the line, but missed a key defensive resource. You thought you were winning an exchange but overlooked their zwischenzug. This is a calculation problem. Your vision is there, but your technique needs work.

Opponent just played: Rad1 (threatening Qxd6)

Passive defensive options: ...Rfd8, ...Rad8

Candidate forcing moves:

Checks: None

Captures: ...Rxa2(??)

Threats: ...d5, ...b5

The best forcing line: 1...d5 2. Bb3 Ba6! skewering white’s queen to their f1-rook and winning the exchange after the queen moves

Even if the opponent makes a threat, you should still look for forcing moves before automatically playing a purely defensive move. Playing 1...Rfd8 or 1...Rad8 does defend against their threat but misses a chance to win material.

Mistake Diagnosis

If you missed a tactical opportunity for yourself, whether you never looked for forcing moves or you calculated the sequence incorrectly, label it: Bucket: Step 2 breakdown.

Step 3: “If nothing tactical: what improves my position most?”

Here’s where many players get lost. You’ve checked for opponent threats (Step 1) and scanned for your own tactics (Step 2). Nothing urgent emerged. Now what?

When there’s no forcing continuation, you’re choosing among plans and improvements. The players who handle these positions well have a simple hierarchy:

Improve your worst-placed piece. Look at your position and ask: which piece is doing the least work? Can you move it somewhere more active? This is often the single most useful approach in quiet positions.

Attack or exploit a weakness. Does your opponent have a backwards pawn, an exposed king, a weak square? Can you put pressure on that weakness or maneuver toward it?

Restrict your opponent’s plan. If you identified their idea in Step 1, can you prevent it? Prophylaxis (stopping your opponent from improving their position) is just as valuable as improving your own.

If you want more information about these three questions then you can check out this previous article I wrote: https://chesschatter.substack.com/p/these-3-questions-will-help-you-play

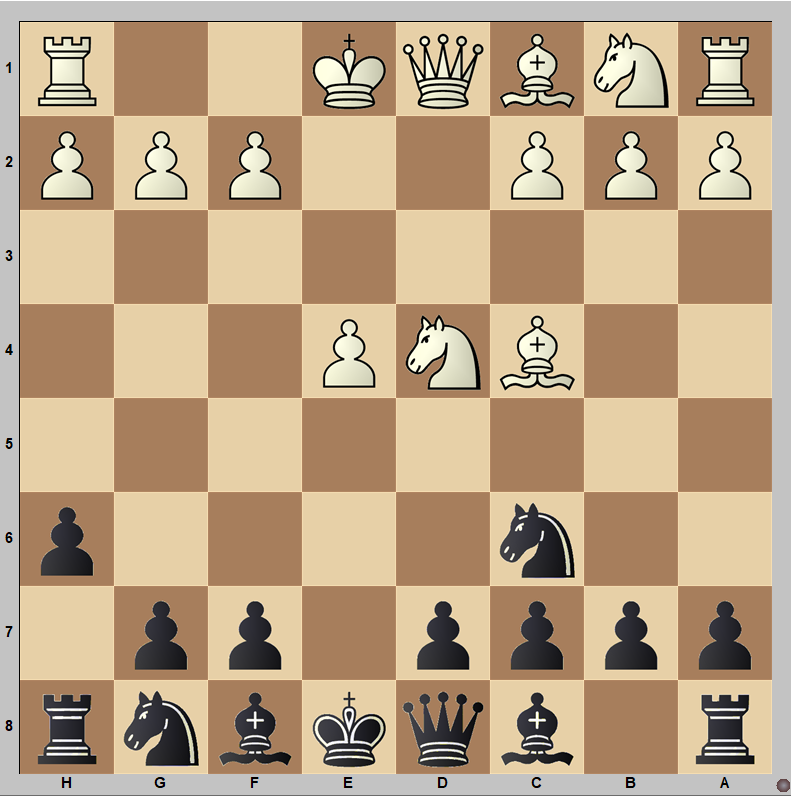

No good forcing moves, so what’s the best improvement?

Identify:

(a) Worst piece: The knight on d8 has ended up on the back rank and isn’t contributing to the position.

(b) Opponent weakness: Their kingside and specifically the light-squares on h3/f3

(c) Opponent’s plan: Nothing is really jumping out here. Maybe White wants to play Qd7 but we can cross that bridge if it happens.

Best move + plan in one sentence: 1...Ne6 with the plan of ...Ng5-f3 or h3, activating the knight while maintaining pressure on white’s kingside weaknesses.

Mistake Diagnosis

If you made a strategic error (improved the wrong piece, chose a bad plan, or missed the most logical positional improvement) label it: Bucket: Step 3 breakdown.

Step 4: “Blunder check: how does my opponent respond?”

This is the step that saves games. You’ve found your candidate move. Before you play it, run through this mini-script:

The Blunder-Check Questions:

What are my opponent’s forcing replies? After your move, what checks, captures, and threats do they have? This mirrors Step 2, but from their perspective.

Did my move leave something hanging or undefended? Count the defenders on your pieces. Did your move accidentally remove a defender from something important?

What changed after my move? Did you open a line toward your king? Create a weakness? Allow a piece into your position?

This doesn’t need to take long. With practice, it becomes a quick scan that catches most one-move blunders before they happen.

Your candidate move: 1...Bc5, developing the bishop and attacking white’s d4-knight.

Opponent’s best reply you missed: 2. Bxf7+! checking your king and pulling it up the board. After 2...Kxf7 3. Qh5+ forks your king and undefended c5-bishop. Once you defend against the check and White captures the bishop, you will be down a pawn with bad king safety too.

Why it works: You developed your bishop to an undefended square, focusing on your own threat (capturing the d4-knight) but didn’t think about white’s forcing move options

What you should play instead: Develop your knight with 1...Nf6 to defend the h5-square and target white’s e4-pawn. Later you can play ...Bc5 or ...Be7 without worrying about Qh5 ideas as much.

Mistake Diagnosis

If you blundered material because you didn’t think about how your opponent would respond to your move, label it: Bucket: Step 4 breakdown (failed blunder check).

Post-Game Analysis: Classify Every Mistake in Two Layers

The four-question framework doesn’t just help you during games. It transforms how you analyze afterward.

But I want to add another layer to this system which is one that I’ve found incredibly useful for understanding not just what went wrong, but why.

Layer A: Which thinking step failed?

This is your four buckets: Step 1, Step 2, Step 3, or Step 4. You now have the language to categorize where your thought process broke down.

Layer B: “Got It Wrong” vs “Didn’t See It”

This layer comes from Nick Vasquez’s excellent Substack post “Making the List”. His classification is beautifully simple:

Got It Wrong: You saw something, but you chose wrong, miscalculated, or missed a defensive resource. The idea was on your radar but you handled it incorrectly.

Didn’t See It: This was a blind spot. You never noticed the idea existed. The possibility never entered your consciousness.

How the Two Systems Work Together

Here’s where this gets powerful. By combining both layers, you get precise diagnoses:

Step 1 + Didn’t See It = You didn’t notice your opponent’s threat at all. This is often a scanning/attention issue. You need to train yourself to pause and actually look at what changed.

Step 1 + Got It Wrong = You saw the threat but picked the wrong defense. This is a calculation or decision issue. You need to work on evaluating defensive options more accurately.

Step 2 + Didn’t See It = You never considered forcing moves. The tactical pattern didn’t occur to you. This points to a knowledge gap or a habit gap as you’re not looking for tactics consistently.

Step 2 + Got It Wrong = You found the tactic but calculated it incorrectly. Your pattern recognition is working; your calculation skill needs improvement.

Step 3 + Didn’t See It = You missed the right plan or piece improvement entirely. This is an experience or positional knowledge gap.

Step 3 + Got It Wrong = You understood the plans but chose the inferior one. Your evaluation or judgment needs refinement.

Step 4 + Didn’t See It = You didn’t ask “what’s their reply?” This is a discipline and habit mistake. You’re not running the blunder-check step consistently.

Step 4 + Got It Wrong = You did blunder-check but miscalculated their best response. Your habit is solid but your calculation under that specific time pressure needs work.

The beauty of this combined system is that you don’t need dozens of categories to understand your mistakes. Two simple labels (which step failed and whether you saw the issue) give you everything you need to direct your training.

A Simple Template You Can Copy

Here’s a template you can paste into a document and use after every serious game:

My Mistake Log

Move number + position link/diagram: _

Which step broke? (1/2/3/4): _

Got it wrong or didn’t see it? _

One-sentence fix (what to do next time): _

Training prescription (tactics / threat scan / positional study / slower time control): _

Fill this out for every significant mistake. Within a few weeks, you’ll start seeing patterns. Maybe you keep failing Step 1 with “didn’t see it” which means you need to slow down and actually look at your opponent’s moves before thinking about your own plans. Maybe you’re consistently in the Step 2/Got It Wrong bucket which means it’s time to focus on deeper calculation training, not more pattern recognition.

The diagnosis tells you exactly what to practice.

If you're looking for a tool to help with your post-game analysis, check out Chessalyz.ai. We’ve designed it to help you break down your games and understand where things went wrong. As you review your games, make it a habit to classify each mistake yourself using the two systems we covered: which step broke down (1, 2, 3, or 4) and whether you "got it wrong" or "didn't see it." That self-diagnosis is where the real learning happens. We're actually working on building mistake classification directly into the Chessalyz analysis process, but for now the manual approach works great and doing it yourself forces you to engage with your errors more deeply.

Make It a Habit, Not a One-Time Trick

The goal isn’t to consciously run through these four questions for the rest of your chess life. The goal is to make them automatic.

Right now, when you sit down at the board, you probably have some default way of approaching each move. Maybe it’s loose, maybe it’s inconsistent, maybe it varies with your mood or time pressure. This framework gives you something solid to replace that with.

Here’s how to train it:

In slower games: Force yourself to ask all four questions on every move. It will feel tedious at first. That’s fine. You’re building the neural pathways.

During puzzles: Before solving, ask Step 1 (what did “my opponent” just do with their last move?). After finding the solution, ask Step 2 (what forcing moves do I have?) and finally, ask Step 4 (how would they respond if I played moves A/B/C?). This trains the thinking system even outside of games.

In blitz: You won’t have time for conscious questioning, but if you’ve trained the system in slower formats, parts of it will fire automatically. That’s when you know it’s working.

The players who blunder less aren’t necessarily more talented. They’ve just built better habits. They ask the right questions automatically, without thinking about it. Every time you run through this flowchart, even when it feels unnecessary, you’re one step closer to making it instinctive.

Four questions. Every turn. That’s all it takes to play cleaner chess.

What step do you find yourself breaking down on most often? Drop a comment below! I’d love to hear what patterns you’re noticing in your own games.

If you're interested in more articles like this, check out my Substack "Chess Chatter" here: https://chesschatter.substack.com/

You may also like

WFM fla2021

WFM fla20216 Tips to Stop Throwing Won Positions in Chess

We’ve all been there: a winning position... and somehow it slips away. Chess is cruel, but the lesso… FM MattyDPerrine

FM MattyDPerrineThe Chess Cookie Jar

Why your brain forgets your best chess and how to fix it FM MattyDPerrine

FM MattyDPerrineWhat If Your Biggest Chess Problem Has Nothing to Do With Chess?

How out-of-game issues sabotage your results and what to do about them thibault

thibaultHow I started building Lichess

I get this question sometimes. How did you decide to make a chess server? The truth is, I didn't. IM datajunkie

IM datajunkieWhy your tactics aren’t improving

The 4 fixes that can help you become a tactician FM MattyDPerrine

FM MattyDPerrine