Op1 - Partial 8-piece tablebase available

63 TiB of chess knowledge sent across the Atlantic and now available on the Lichess analysis boardIn a collaboration with Marc Bourzutschky, we can now expand Lichess's tablebase interface to a large subset of practical 8-piece positions. The tables are publicly available: for download (63 TiB); via the tablebase API for developers; and right on the analysis board and the mobile app.

Marc has a long history of contributions to endgame theory, including early work on 7-piece tables over twenty years ago. In 2021, he announced results from first explorations into 8-piece territory.

In 2025 Niklas Fiekas started working with Marc to bring the tables online.

The subset: Op1

The tablebase covers those 8-piece positions that have at least one white and one black pawn that oppose one another, impeding each other’s path to promotion. We refer to such pawns as an opposing pair, and to positions that contain at least one opposing pair as op1.

An opposing pair will be on one of the files a-h. For a given file there are 15 opposing pair positions. For example, on the a-file a white pawn on a2 and a black pawn on a3 form an opposing pair. Denoting this opposing pair by a2/a3, the remaining 14 opposing pairs on the a-file are a2/a4, a2/a5, a2/a6, a2/a7, a3/a4, a3/a5, a3/a6, a3/a7, a4/a5, a4/a6, a4/a7, a5/a6, a5/a7, a6/a7.

Opposing pairs are thus a generalization of the concept of blocked pawns. The key feature of an opposing pair is that neither of the two pawns in an opposing pair can promote unless there is an intermediate capture, even if the pair is far apart like a2/a7. By contrast, a3/a2 (white pawn on a3 and black pawn on a2) is not an opposing pair because each pawn might be able to promote without any intermediate captures.

In the tablebase we exclude extremely imbalanced positions where one side has just one pawn, i.e., endings like KQRBNPvKP. Most likely such lopsided positions are not very interesting.

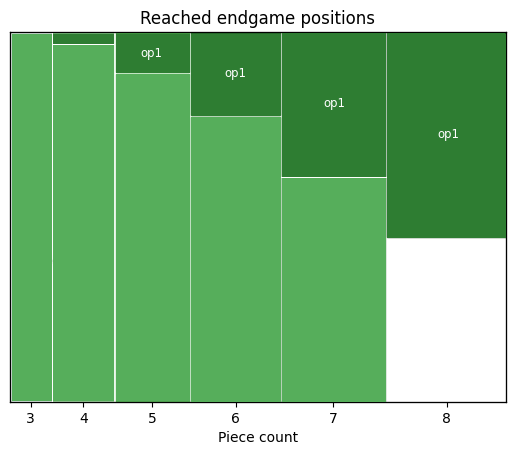

Empirically, about half of all 8-piece endings reached in practical games are op1. This is confirmed by scanning game databases such as Chessbase’s megabase and the CCRL database of engine games. Indeed, slightly more than half of the 8-piece endgames reached on Lichess are op1, as shown in the graph below. So 8-piece op1 adds a good chunk to our existing 7-piece tablebase coverage via Syzygy.

Proportion of 3-8 piece endgames and respective op1 endgames reached on lichess.org in 2025

Proportion of 3-8 piece endgames and respective op1 endgames reached on lichess.org in 2025

Op1: Some practical examples

As an op1 example with only two pawns consider the following position from the 16th game of the 1990 world championship match between Garry Kasparov and Anatoly Karpov:

The opposing pair consists of the white pawn on g4 and the black pawn on g6. In the game White played quite accurately to achieve the win.

As an op1 example with three pawns consider the following position from a game between Tigran Petrosian and Viktor Korchnoi played in 1976:

The opposing pair consists of the white pawn on g5 and the black pawn on g6. Black has an additional pawn on f7 that is not opposed by a white pawn and could thus in principle promote without any intermediate captures. However, such quiet promotions would not affect the opposing g-pawn pair, so still lead to another op1 position with only two pawns where the black f-pawn has been replaced by a Knight, Bishop, Rook, or Queen. The tablebase shows that this position is winning for White, but the win is quite tricky even with the help of a chess engine. The game ended in a draw.

In the previous position the opposing pair happens to also be a blocked pawn pair. This is not necessary for the position to be op1. Consider the following position from a game Korchnoi-Ponomariov played in 2001 that has the same material distribution:

The opposing pair consists of the white pawn on g4 and the black pawn on g7. The op1 tablebase shows that the position is won for White. In the game White did manage to win, but only after several errors by both sides.

For an op1 example with two pawns in addition to the opposing pair consider the following position from the 9th game of the 1984 Karpov-Kasparov world championship match, one of the most famous endings ever played:

The opposing pair consist of the white pawn on b4 and the black pawn on b5. Non-capturing moves by the two additional white pawns don’t affect the opposing pair. It took about thirty years after the game to convincingly conclude that 66...Bh1!! is the unique drawing move. The op1 tablebase confirms this conclusion. FinalGen, a software program developed by Pedro Pérez Romero in 2012, was the first computer tool that could resolve this position. However, FinalGen only works with endings where each side has exactly one non-pawn piece. Furthermore, in FinalGen each position has to be generated from scratch rather than being available with a simple table lookup like the op1 endings.

For an example where both sides have two pawns consider the following position from a game between Peter Leko and Alexander Beliavsky played in 2000:

Here there are two opposing pairs, g2/g7 and h3/h5. The position is op1 because the only requirement is that there is at least one opposing pair, even if there is more than one. Normally such positions are expected to be drawn because Black has the "right" colored Bishop, i.e., the same color as the corner square behind his rook pawn. However, in this particular position White could actually have won. In the past, complex versions of such endgames could be analyzed using FinalGen with a lot of effort, but with the op1 tablebase they can be evaluated instantly.

For an op1 example containing six pawns, consider the following position from a game between Hua Ni and Pin Wang played in 2001:

In addition to the opposing pawn pair on e4 and e5, each side has two passed pawns. In fact, both sides ended up promoting one of their pawns to a queen before any captures occurred. This position, as well as the queen endings that resulted from the promotions, can be found in the op1 tables. The position is a draw.

Finally, the position below is an example of a position that is not op1 because there are no opposing pairs, and is therefore not included:

Generating the op1 tablebase

The previous sections introduced op1 endings and should provide enough detail to understand what is contained in the op1 tablebase to be able to use it. In this section we provide a little more detail on how the op1 tablebase was generated, and how it relates to the broader set of all 8-piece tablebases. You can skip this section if you are not interested in those details.

Tablebases are generated backwards from checkmate or known wins, using retrograde analysis. To generate an 8-piece tablebase, we need to know all the 7-piece endgames that can result from the 8-piece endgame by capture, as well any 8-piece endgames that can result from a promotion (including underpromotions.)

The process for generating the complete 8-piece tables (not just the op1 tables) would thus proceed as follows:

- Generate all 8-piece endings without pawns. Since there are no promotions possible, we just need the 7-piece tablebase to resolve captures.

- Generate all 8-piece endings with one pawn. For example, for endings with one white pawn we need to know the result of any promotion of that pawn, to Queen, Rook, Bishop, or Knight. But the endings after all promotions are 8-piece endings without pawns, and we have all those endings available now from step 1.

- Generate all 8-piece endings with two pawns (two white pawns, or two black pawns, or one white and one black pawn). Any promotion from such an ending will result in an 8-piece ending with one pawn, which we have generated in step 2.

We can continue this process until all 8-piece endings with 6 pawns have been resolved and we are done (recall that two of the 8 pieces are kings.)

The total number of 8-piece positions is enormous. Kirill Krykov computed the number of distinct legal positions exactly, arriving at about 3.8x10^16 (38 followed by 15 zeroes). This is almost a factor of 100 larger than the number of distinct legal 7-piece positions of about 4.2x10^14. Kirill’s count includes positions with castling rights which we ignore, but those positions represent less than 0.2% of the total.

In general it is not possible to skip any of the steps during generation without risking that some positions will be evaluated incorrectly because of a missing underpromotion. For example, to correctly generate all KRPPPvKRP positions requires generating 175 8-piece endings that can result from all sequences of possible promotions. If we limit ourselves to queen promotions we can dramatically reduce the number of 8-piece endings needed to 8. However, even though forced underpromotions are relatively rare, some positions will then be evaluated incorrectly.

Op1 endings represent a small subset of 8-piece endings that are evaluated correctly and are also relevant in practice.

To generate op1 tables, the first step is to generate 8-piece op1 endings that have only one opposing pair, while the remaining pieces are non-pawns. Because neither pawn can promote without an intervening capture we don’t need to know any 8-piece endgames with one or zero pawns. We can resolve any captures because those result in 7-piece endings. Furthermore, the number of positions for a given op1 endgame is much smaller than for the corresponding ending without the op1 restriction, as shown by the following simple calculation. The number of ways two pawns can be put on the board without restriction is 48*47=2,256, because the first pawn can be put on any square between a2 and h7, and the second pawn can be put on any square not occupied by the first pawn. For opposing pairs, both pawns have to be on one of the 8 files, a-h. We showed in the previous section that there are 15 possible opposing pairs on a given file. So overall there are 8*15=120 opposing pairs, which is about 5% of the total number 2,256.

The second step is to resolve all op1 endings that contain an additional pawn besides the opposing pair. Any promotions by that pawn that don’t involve intervening captures don’t affect the op1 nature of the opposing pair and therefore result in an op1 ending we have already generated in step 1, while any captures of course lead to 7-piece endgames that we already know. A mathematician might say that the set of op1 positions is closed under non-capturing moves. We can keep adding pawns this way, and so generate the complete set of op1 positions, including those with 6 pawns.

The op1 tablebase has about 5.0x10^14 legal positions, so is only slightly larger than the 7-piece tablebase (this number would be about 20% higher if we included lopsided endings where one side just has a single pawn, such as KQRBNPvKP.) This is only 1.3% of all legal 8-piece positions from Kirill Krykov’s calculation. The reason that, nevertheless, roughly half of 8-piece endgames reached in practical games are op1 seems to be that in the starting position with 32 pieces there are 8 opposing pawn pairs, and there is a high likelihood that at least one opposing pair survives until there are only 8 pieces left.

The metric: Depth To Conversion (DTC)

Tablebases generally provide a value measuring the distance to victory. If we are winning, we should pick moves to minimize the distance to get there. There are multiple common ways to measure that distance.

Depth to Mate (DTM): The most direct, simply the number of moves to checkmate.

Depth to Conversion (DTC): The number of moves to checkmate, or to a (still winning) capture, or to a (still winning) promotion. There is a limited number of pieces to capture and pawns to promote, so eventually checkmate will be reached. Thinking about converting to simpler winning endgames comes pretty natural to chess players. This is the metric used in the newly available op1 tables.

Depth to Zeroing under the 50 move rule (DTZ50): The number of moves to checkmate, or to a (still winning) capture, or to a (still winning) pawn move. The number of possible future pawn moves is also limited, so eventually checkmate will be reached. Unconditionally moving pawns as early as possible does not always look natural to human players, but of the given metrics it's the only one that reliably avoids the 50-move rule where possible. This is the metric used in the existing 7-piece Syzygy tables.

Wins prevented by the 50-move rule may still be interesting (or indeed particularly interesting). The tablebase explorer on Lichess always shows any uncertainty with regard to the 50-move rule.

Collaborating on 63 TiB of data

Even in 2025, sharing large amounts of data on a budget is quite challenging, especially when neither Marc in the US nor Niklas in Europe had fiber internet in their homes. We considered various providers who would pick up data to upload, or would allow bringing data on-site to upload, but ultimately settled on sending three hard drives in a box.

Until then, most of the tablebase server development was possible with small slices shared online. The final upload to Lichess servers was done using the fiber connection of friends and family.

Improvised setup hogging ~500 Mbit/s upload bandwidth for two weeks

Probing code

The tables are organized into 575 directories by material combination, each containing separate files for the 1806 possible distinct king positions. Such a file has a header with some metadata, an index of blocks to facilitate point lookups, and then ZStandard compressed blocks with the DTC values. Draws and losses are marked with a special value and can be distinguished by probing the mirrored position.

A tablebase query on Lichess follows this path:

- HTTP call to lila-tablebase (Rust, axum, tokio).

- lila-tablebase calls out to Syzygy tablebases, Gaviota tablebases, and now also op1 tablebases, if the position or any of its children is op1.

- Such internal op1 calls go to the server that has all the tables, running https://github.com/lichess-org/op1 (same tech stack).

- The op1 service applies many of the lessons learned from optimizing 7-piece tablebases, focusing on tail latency rather than throughput. Each child position is probed in parallel, so the I/O scheduler gets to make a better plan.

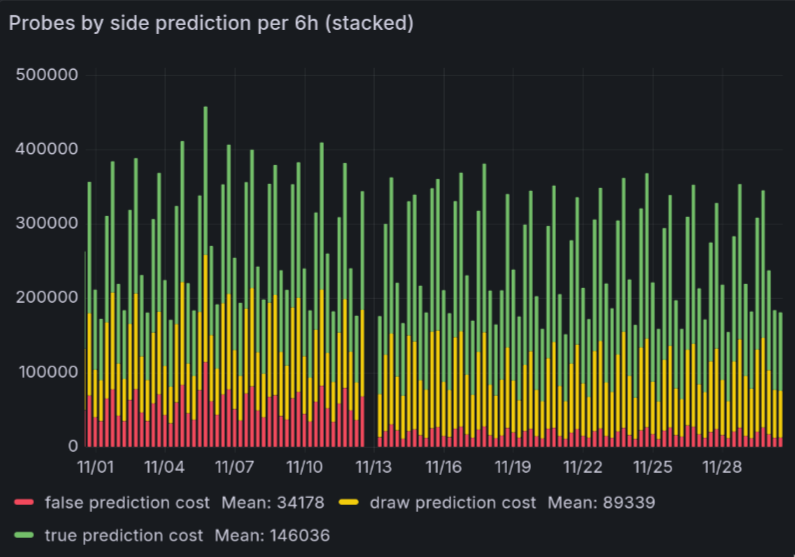

- For each probe, we try to guess which side is winning. A correct guess will require one table lookup. An incorrect guess will see the special marker value and then trigger a second lookup for the mirrored position. Draws always need both of those table lookups.

- To probe the individual table, the service uses Marc's indexing code via C FFI, obtaining the index that will have the DTC value.

- A binary search in the table header delivers the offset of the corresponding compressed block. The table headers are loaded into RAM lazily, but at 128 GiB the server has just enough RAM to keep them indefinitely.

- The block is read from page cache or disk. We always read the entire block, to not risk a second round trip, but then decompress just enough to find the value for the index and return it.

Switching from win predictions based on material balance to material balance after 1-ply search. (The tablebase has been online for a while, labelled as experimental).

Switching from win predictions based on material balance to material balance after 1-ply search. (The tablebase has been online for a while, labelled as experimental).

Outlook

While full 8-piece tables are not on the horizon, two smaller additions may be feasible: First, 7-piece DTC, for completeness. Second, generalizing the idea to multiple pairs of opposed pawns. For example, 9-piece op2 positions contain at least two opposing pairs such that any capture leads to an op1 position. Such tables are also relatively straightforward to compute and we have already done so for configurations that don’t contain any pawns other than those in the two opposing pairs. As an example, consider the following position from the game Magnus Carlsen vs Levon Aronian, played in the 2012 Tata Steel tournament:

This position has 9 pieces, but because any capture leads to an op1 ending we are able to resolve this ending completely. The position is winning for White, but both players and a commentator missed a couple of things.

Another complicated 9-piece op2 example is the following position that occurred in a game between Michael Adams and Hannes Stefansson, played in 2023:

White is winning according to the tablebase, but the game was eventually drawn.

Niklas is also working on a standalone frontend https://op1-tables.info/, to show some additional stats that can't be crammed into the analysis page. So far only links to the maximum DTC positions are complete. In the meantime you can find the raw data in .w.* and .stats files next to the table directories.

You may also like

Lichess

LichessInterview: Ju Wenjun - Women's World Chess Champion 2025

Lichess interviewed GM Ju Wenjun after she won her fifth Women's World Chess Championship title. thibault

thibaultHow I started building Lichess

I get this question sometimes. How did you decide to make a chess server? The truth is, I didn't. Lichess

LichessLichess: End of Year Update 2025

Is it just us, or has this year flown by? As we say goodbye to 2025 and enter 2026, let's look back … Lichess

LichessFIDE World Cup R4: Praggnanandhaa, Keymer, Vachier-Lagrave, Blübaum Eliminated

GM Daniil Dubov eliminated GM Praggnanandhaa R, while GM Andrey Esipenko got the better of GM Vincen… CM HGabor

CM HGaborHow titled players lie to you

This post is a word of warning for the average club player. As the chess world is becoming increasin… ChessMonitor_Stats

ChessMonitor_Stats